During the 2020 coronavirus lockdown, I bought some old Pocket PC-based mobile devices off eBay for a bit of fun, and wanted to see whether I could get them to run my own programs. This page details my explorations into this.

Devices

The two devices I bought are:

HTC Advantage X7500

£45. Who needs an iPad Pro when you have one of these?

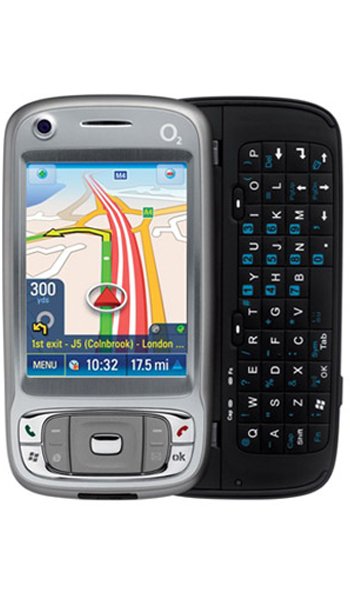

O2 XDA Stellar

£7.99. Listed as spares/repairs because the seller didn’t have the cables or sync software, but it turns out it works just fine. Bargain.

File Transfer

First of all, we need to establish how to put software onto the devices. It would be nice to be able to plug them into the computer and just have them show up as USB mass storage devices, but apparently that’s too much of an ask for 2007-era tech.

Either ActiveSync or the newer Windows Mobile Device Centre (with the option of additional driver upgrades) must be installed in order to communicate with the devices. This seems to be a bit of an issue in Windows 10, as the Creators Update broke compatibility with the utility. This StackOverflow question has some good instructions, but I found I also had to follow some more instructions from a page I’ve forgotten the link to:

- Open the Services utility (search

services.mscin the start menu) - Find “Windows 2003-based-device connectivity” and open the properties window for this service.

- Under the “Log On” tab, choose “Local System account”.

- Restart the service.

Even then, connectivity is still spotty - it’ll work sometimes, and other times not, for seemingly no reason. To make things easier, I used one of the times I did have connectivity to install the Mocha FTP server on the devices. Since they’re both able to connect to WiFi OK, it was much easier and more reliable to transfer files using an FTP client.

Note that the FTP server needs the license name freeware and the license key 111425 to bypass the trial state. The website does provide this information, but I missed it the first time I tried to use the application.

One other method, of course, is to copy any applications onto a compatible memory card and then insert this into the device. The XDA Stellar takes MicroSD cards, but the HTC Advantage (which was the one I wanted to use because of the bigger screen) takes MiniSD, which I wasn’t even aware of before buying it. I have no MiniSD cards or adapters at home, and couldn’t be bothered to have to wait for one to be delivered, so I went for the FTP server option instead.

Compilers

The CEGCC project hosts compile tools based on GCC which allow compailation for the Windows CE (Pocket PC) platform. These tools are over ten years old, and after some experiments I wasn’t able to make much progress with them. Luckily you can bypass that grief, along with the early-2000s frame-based website design, by using the much more up-to-date GCC 9.3.0-based project by Max Kellermann. The binaries are pre-built for Debian x64, or can be built from scratch using the GitHub repo.

I created a simple test program on my Ubuntu system using the Debian-based CEGCC compilers, but oddly was unable to FTP to (or even ping) the devices from that system, even though they were definitely on the local WiFi network and had internet access, so couldn’t test it. I don’t know whether this is because Windows has some compatibility-mode networking layer that Pocket PC devices use but Ubuntu doesn’t?

For better ease of testing, I installed the compilers on a virtual machine within Windows instead, so that I could get FTP access.

EDIT: Turns out FTP isn’t always reliable on Windows either… I’m starting to suspect it’s the WiFi connection to the device that’s the problem, given it’s using 2007-era WiFi protocols and drivers.

The following sections document the steps required to get the compilers to work.

Stow

Since the binaries are provided as simple files in a tarball, they must be installed into a recognised directory on the system. I was reluctant to just lob them into the general bin and lib directories, but after a bit of searching discovered the stow tool. This manages creating symlinks to self-contained sets of binaries such as these compile tools: if you “install” binaries using stow, it creates symlinks in the binary directories recognised by the system that point to your target programs, and “uninstalling” them simply removes the relevant symlinks.

To use stow to install the compiler binaries, follow these steps:

- Extract the contents of the tarball to a specific directory, eg.

mingw32ce. - Copy this directory to the

stowdirectory (this will probably requiresudo). By default, this is/usr/local/stow. - Open a terminal in the

/usr/local/stowdirectory. - Run

sudo stow -S mingw32. Symlinks will be created in the relevant directories (/usr/local/bin, etc.).

Sample Program

A simple program that utilises the WindowsCE API to show a message box is as follows:

#include <windows.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

MessageBox(nullptr, L"This is a Pocket PC application.", L"Message", MB_OK);

return 0;

}

Save this in a working folder as main.cpp.

The CEGCC compiler for C++ code is arm-mingw32ce-g++. To compile the code, run:

$ arm-mingw32ce-g++ -o test.exe main.cpp

“Archive has no index”

The first time you run this code, you’ll likely get an error that looks like:

/usr/local/stow/mingw32ce/bin/../lib/gcc/arm-mingw32ce/9.3.0/../../../../arm-mingw32ce/bin/ld: /usr/local/stow/mingw32ce/bin/../lib/gcc/arm-mingw32ce/9.3.0/../../../../arm-mingw32ce/lib/libstdc++.dll.a: error adding symbols: archive has no index; run ranlib to add one

collect2: error: ld returned 1 exit status

I don’t know much about the specifics of this, but I think it’s to do with the fact that the static libraries provided with the compiler have not had their metadata built. For more useful information about what a static library .a file actually is and why this process is required, check out this StackOverflow answer.

To fix this, run:

$ sudo arm-mingw32ce-ranlib /usr/local/stow/mingw32ce/arm-mingw32ce/lib/libstdc++.dll.a

For me, this then popped up an additional error:

arm-mingw32ce-ranlib: error while loading shared libraries: libfl.so.2: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

This is because the flex library (for lexer support) was missing from my system. I installed it using sudo apt install flex, ran the previous command again, and it worked.

Now, after re-running the g++ call, we get a test.exe executable. If this is copied onto the device and run, a message box will be displayed!

“Error while loading shared libraries: libmpc.so.3”

I also tried the above on Windows Subsystem for Linux 2, out of interest. Upon first attempting to compile the test application, I got the error:

/usr/local/stow/mingw32ce/bin/../libexec/gcc/arm-mingw32ce/9.3.0/cc1plus: error while loading shared libraries: libmpc.so.3: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

This was fixed by installing the libmpc-dev package: sudo apt install libmpc-dev.

Programming API

A useful document concerning the Windows API with respect to Windows CE can be found here. Microsoft API documentation for Windows CE can be found here.

Creating a Window

It seems to be very easy to create a floating window for Windows CE, but quite difficult to work out the correct set of parameters to create a normal fullscreen window with an “OK” button in the top right. After some experimentation, I found that the following call seems to work:

CreateWindow(L"WindowClass", // Class

L"WindowTitle", // Title

WS_VISIBLE, // Style

CW_USEDEFAULT, // X

CW_USEDEFAULT, // Y

CW_USEDEFAULT, // Width

CW_USEDEFAULT, // Height

NULL, // Parent window

NULL, // Child/menu

hApplicationInstance, // Instance passed into WinMain

NULL); // User data

The crucual parameter appears to be the window style WS_VISIBLE. If this is ommitted, the window is displayed as floating and without a close button, requiring it to be killed through the task manager.

Using Windows Libraries

Beyond the core functionality of the Windows API, certain controls will require linking to the Windows API libraries. I got a bit confused at first regarding how to do this, but it turned out it was just because of my lack of experience in using the GCC command line.

If you want to link with what would normally be CommCtrl.dll on Windows, the compiler invocation would look something like this:

# Compile the source file into an object file (main.o)

$ arm-mingw32ce-g++ -c main.cpp

# Link main.o into an executable called test.exe, linking also against

# libcommctrl.a The linker -l option automatically adds the "lib"

# prefix and the ".a" suffix, so all you need to supply is -lcommctrl

# VERY IMPORTANT: the -l option must go *after* the object files, or

# it will be ignored!

$ arm-mingw32ce-g++ -o test.exe main.o -lcommctrl

Note that the CEGCC toolchain provides all the relevant Windows modules as static libraries, as far as I can see. We may need to see what can be done to link against these dynamically in future.

Showing the Bottom Command Bar

By default, a standard window created with the CreateWindow() function call will not display the command bar at the bottom of the screen. However, while searching through the exposed functions in the CEGCC static libraries, I stumbled across libaygshell.a and looked up what it was used for. This page notes that:

aygshellwas originally some shell extensions designed for the Windows Mobile environment. … As an example theSHCreateMenuBar()API which creates menubars at the bottom of your window is part ofaygshell. Standard Windows CE applications would typically use something likeCommandBar_Create()instead (which places the menubar at the top of the window).

For documentation on the API, see these Microsoft pages. The following sample code shows how to create a menu bar, which is adapted from this page.

LRESULT CALLBACK WindowProc(HWND hwnd, UINT uMsg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

switch (uMsg)

{

case WM_CREATE:

{

// To create a menu bar, this struct is used for API operations.

SHMENUBARINFO mbi;

ZeroMemory(&mbi, sizeof(mbi));

mbi.cbSize = sizeof(mbi);

// Parent window that will own the menu bar.

mbi.hwndParent = hwnd;

// Some unique ID for the bar, which can be used to distinguish

// UI elements between one another.

mbi.nToolBarId = 1;

// The application instance that owns the resources that the bar uses.

mbi.hInstRes = hInstance;

// This seems to be the most important property regarding how the bar looks.

// Several flags are abvailable to control its appearance: see

// https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/embedded/aa453721(v%3Dmsdn.10)

// It appears that SHCMBF_EMPTYBAR works the best.

mbi.dwFlags = SHCMBF_EMPTYBAR;

// If this call was successful, mbi.hwndMB holds a handle to the bar that was created.

if ( SHCreateMenuBar(&mbi) )

{

TBBUTTON tbButton;

ZeroMemory(&tbButton, sizeof(TBBUTTON));

// The method of creating a button is actually quite involved. Luckily, after stumbling

// upon the cpp.hotexamples.com link, I learned that it involves the following:

// This is a pre-defined constant for buttons that do not use bitmaps.

tbButton.iBitmap = I_IMAGENONE;

// Make sure the button starts out enabled.

tbButton.fsState = TBSTATE_ENABLED;

// Make it look like a button, and take up the correct amount of space.

tbButton.fsStyle = BTNS_BUTTON | BTNS_AUTOSIZE;

// I think this is arbitrary user data stored on the button.

tbButton.dwData = 0;

// Some ID representing the button's command. This is passed into the

// WindowProc when the button is pressed, and can be handled by catering

// for the WM_COMMAND message.

tbButton.idCommand = 2;

// In order to display a string, the string must first be registered and given a handle.

// The button then stores this handle, instead of storing the string directly.

tbButton.iString = ::SendMessage(mbi.hwndMB, TB_ADDSTRING, 0, (LPARAM)(TEXT("TEST")));

// We ask how many buttons there are in the toolbar. We don't strictly need to do this in

// this example, but if we pass the count as the first message argument below, it ensures

// that the new button will always be added to the end of the menu bar, after all other

// buttons.

int buttonCount = ::SendMessage(mbi.hwndMB, TB_BUTTONCOUNT, 0, 0);

// Finally, we send a message to add the button we just set up.

::SendMessage(mbi.hwndMB, TB_INSERTBUTTON, buttonCount, (LPARAM)&tbButton);

}

break;

}

case WM_PAINT:

{

PAINTSTRUCT ps;

HDC hdc = BeginPaint(hwnd, &ps);

// Fill the entire window and then draw the menu bar.

// There is no need to adjust the rect that is filled here -

// it appears to already be correctly sized to take into account

// the menu bar.

FillRect(hdc, &ps.rcPaint, (HBRUSH) (COLOR_WINDOW+1));

DrawMenuBar(hwnd);

EndPaint(hwnd, &ps);

break;

}

}

}

Strings: Unicode, wchar_t, UTF-8, UTF-16… What the hell is all this?

Man, this is a pain. This is a paaaaain. It’s super-easy to get confused with all of these different concepts, so here’s my attempt to solidify my knowledge.

1. “Unicode” has nothing to do with how strings are represented on the device

There’s a lot of confusion of terminology, both in my head and also on the pages I’ve been reading, when discussing “Unicode” text. What Unicode actually is is a defined mapping for every type of character used in human languages. Each character is assigned a “code point”, which is essentially a number, and it is up to the device in question to encode that number in a way that can be used within computer programs.

2. The “UTF-Something” variants specify some possible encodings

Here, it is important to make a distinction between a character and a byte, since in ASCII text (which came before Unicode), a character and a byte are essentially the same thing. This can be seen by the fact that a single byte in C is referred to as a char.

In the Unicode sense, a “character” refers to something that is used to form words in part of a written language. A “byte” is a unit of computer memory. One character in a string in your program may take up more than one byte; exactly how many bytes it does take up depends on how it is encoded.

One more, potentially confusing aspect in all of this is the consideration of how strings are actually indexed in languages like C. A string is nothing more special than an array of bytes that is interpreted as text, and back in ASCII land, each array element corresponds exactly to one character. If the size of each element in the array is not actually large enough to support all the characters represented by Unicode, certain characters will be encoded using more than one consecutive element. This means that the length of the string in terms of readable characters is no longer equal to the length of the array in terms of elements.

So, just to solidify these terms once again before we go on:

- Character: A symbol written down in a human language, where multiple characters form words.

- String element: One individually indexable part of a string. May not map one-to-one onto characters.

- Byte: A unit of computer memory. Strings may use one byte per element, or more than one.

The UTF encoding standards were at least partially designed (as far as I can deduce) to allow programmers to choose to retain the one-to-one mapping between string elements and characters if they wanted to. Unfortunately, in practice this doesn’t seem to work very well. Consider the three variants:

- UTF-8 uses 8 bits (one byte) per string element. The first 128 values of a UTF-8 character map exactly onto ASCII characters, so UTF-8 is 100% ASCII-compatible. Characters whose codes exceed the range of 8 bits are composed of multiple bytes (and so multiple string elements) - that’s just what you get by using this encoding.

- UTF-16 uses 16 bits (two bytes) per string element. Unfortunately, 16 bits is also not enough to encompass all possible Unicode characters, so the possibility of one character spanning multiple string elements still remains. UTF-16 strings are also incompatible with ASCII.

- UTF-32 uses 32 bits (four bytes) per string element. This covers all Unicode characters, but uses up a lot of memory, so basically no-one uses it. Again, it is incompatible with ASCII.

The only one of these three variants that actually guarantees that each character maps to one string element is UTF-32, which is the least commonly used.

3. Microsoft’s Unicode support is poorly designed

Microsoft makes wchar_t available in C and C++, which on Windows represents a “wide character” of 16 bits. Unfortunately, on Linux wchar_t is 32 bits, so the two platforms are not inter-operable when using them.

Microsoft also makes available some functions to convert wide character strings to multi-byte character strings. I’m assuming this was to allow developers to work in a “one string element = one character” way with wchar_t, vs. essentially using UTF-8. However, as we know, 16-bit string elements are not large enough to completely eliminate the need for multi-element characters, so it seems a bit pointless.

4. Windows CE is a Unicode platform - sort of

The original CeGCC page states that:

Many applications are currently still coded to cope with one-byte characters. Several operating systems have been providing support for both that traditional way of working, and a more general approach. Windows CE is special in that it only supports Unicode in many of its API’s. This means that an application that wants to create a file must pass the file name as a Unicode string.

What they actually mean by “Unicode” here is unclear, since ASCII strings are technically Unicode if using UTF-8. However, interestingly, the following code exists in the mingw32ce stdlib.h file:

_CRTIMP double __cdecl __MINGW_NOTHROW atof(const char*);

_CRTIMP int __cdecl __MINGW_NOTHROW atoi(const char*);

_CRTIMP long __cdecl __MINGW_NOTHROW atol(const char*);

#if !defined (__STRICT_ANSI__)

#if !defined (__COREDLL__)

_CRTIMP double __cdecl __MINGW_NOTHROW _wtof(const wchar_t *);

_CRTIMP int __cdecl __MINGW_NOTHROW _wtoi(const wchar_t *);

_CRTIMP long __cdecl __MINGW_NOTHROW _wtol(const wchar_t *);

#endif

#endif

When running the mingw32ce compilers, __COREDLL__ is defined, so conversion functions such as _wtoi (wide character string to integer) are not available. Indeed, listing functions from libcoredll.a reveals that only atoi exists, and there are no wide character to integer conversion functions present. There are, however, wide character string manipulation funcions such as wcsncat.

Basically, what the hell is going on with the Windows CE API here is really not clear. It looks as though the most sensible thing to do would be to continue to use wide characters as most Windows applications seem to do, but to convert to multi-byte strings when using functions such as atoi (I think it’s relatively unlikely that incompatible characters will be fed into this anyway).